Behind the Lens: The Incredible Underwater World of Didier Noirot

From the age of 15, Didier Noirot had a dream. Inspired by Jacques Cousteau’s underwater documentaries, he decided that one day he would join the legendary ocean explorer’s diving team on his research vessel Calypso.

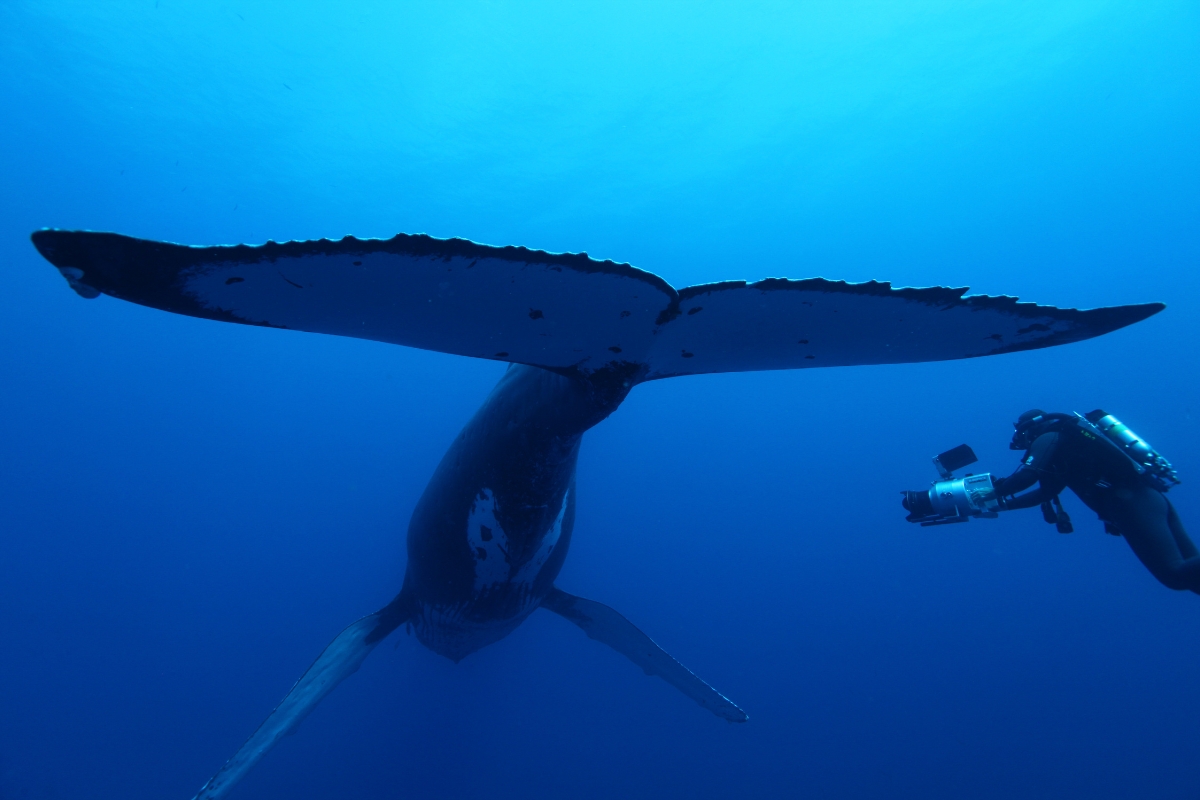

Looking back over his five decades as an underwater cameraman, which saw him not only work closely with Cousteau for 11 years, winning Emmy awards and a BAFTA, but also become the first person to film a humpback whale giving birth, Didier is in reflective mood about his stellar career as he says: “I’ve had an incredible life.”

No-one could argue with that. His work on land as well as in the ocean has seen him up close with orang-utans in Borneo, emperor penguins in Antarctica and chiefly, in the deep alongside humpbacks and southern right whales, filming as far afield as Polynesia, Argentina, Borneo, New Zealand and Australia.

His passion for the ocean started as a boy at the family holiday home in Brittany. “We spent all my school holidays there and it was where I first got into the water as a kid with a mask, fins and a snorkel, one of the old fashioned ones with the ping pong ball in the top,” he recalls.

He tried scuba diving at 18 after wandering into le Martin Pecheur (Kingfisher) fishing and diving shop in Paris and being advised by shop assistant Serge Birre on what to buy and how to use the equipment.

“I bought a 15 litre tank, a regulator and a diving watch. Serge, who is still working today, told me how the tank worked, explained the reserve system for when the air ran out so you could liberate the last 40 bars of pressure - pressure gauges didn’t exist then - and filled the tank with air.

“The next day I went to a fresh water quarry west of Paris and tried everything out. I saw a few fish and after an hour, I had no more air so I pulled down the reserve, the air came through and I slowly came up to the surface. I taught myself to dive, I’m self-made. It was normal then.

“The only people diving were adventurers, pioneers and fit people. Today, you need an instructor and certification like the PADI but at this time, it didn’t exist so we could do whatever we wanted.”

After cementing his diving knowledge at the Glénan diving school in Brittany, he taught underwater photography at Club Méditerranée, travelling to the Red Sea, West Indies, the Bahamas, Mexico and the Maldives.

However, it’s his work with the forefather of scuba diving which really captures the imagination, and Didier is only too happy to share the highlights of their 11 year working relationship, which began in 1986 when he was 28 after he wrote a letter to Cousteau.

“I told him ‘You need me, this is what I can do’, and I sent him 40 duplicates of colour slides and 15 mins of video images. He liked my pictures and asked me to come to his office in Paris. He introduced me to his cameraman Michel Deloire and said, ‘Didier Noirot is leaving with you for New Zealand.’ Then he asked, ‘Didier, when are you free to leave?’ I told him ‘Yesterday’, and I left the next day for New Zealand with the team.”

After deciding he didn’t want to be the cable holder (the lowest job designated to the newest dive team member), he managed to get moved onto the inland diving team, filming the lakes and rivers of New Zealand.

“It was supposed to be a punishment for not doing a good job as the cable guy but I had a good time and I got my chance to film for the first time with the Cousteau camera. They were very happy with the pictures and told me that next time, I could be the stills photographer. I covered the next three expeditions in Polynesia, Australia and Papua New Guinea.”

It was his footage of oyster baskets on a pearl farm in the Gambier Islands in south Polynesia that provided his eureka moment with Cousteau.

“He was at the back of the boat, and asked where I was going. I told him and he told me ‘You piss me off with your photos, take a cinema camera!’ I asked how it worked, as there wasn’t a viewfinder or monitor, and he took it and pointed it at me, saying, ‘Like a machine gun!’

That was my only lesson in underwater filming so I had to get it right.”

Needless to say, Cousteau loved his footage, which was backlit by the sun, telling Didier his camera speed and movement in the water were just right.

Other highlights of his diving escapades include discovering a cave near Sipadan, Malaysia, which had become a turtle cemetery, with 25 skeletons laying mysteriously next to one another. Didier asked for extra time to film there, Cousteau agreed to 10 days and somehow Didier persuaded him to grant three weeks.

“He told me it was impossible but I said ‘I’m staying here to play with your diving toys while you’re editing in Paris.’ He was the most famous man in the world and I spoke to him like that but in the end he agreed.

“His wife Simone also liked me for standing up to him. She was putting her own money into maintaining his boat and in 1972, long before I arrived, she sold all her jewellery to safeguard the team and pay their salaries.

“You could do whatever you wanted on the boat as long as you fitted the mould. If you had the energy and desire to dive and explore, he gave you everything you needed. Cousteau was a very visionary guy. He was one of a kind.”

Didier has worked on wildlife documentaries for National Geographic and Disney as well David Attenborough’s series’ The Blue Planet and Planet Earth, winning a BAFTA for best photography for The Blue Planet, and Emmys for outstanding cinematography for Planet Earth and One Life.

His close encounters with whales include filming two male humpbacks performing a ballet in the water, with one flitting within 10 centimetres of the lens without touching the camera. On another occasion, he kissed a friendly sleeping humpback on the nose as she stayed perfectly still by him.

And in Valdez, Argentina, while filming southern right whales, a calf’s mother came to hover less than a metre above him, resting happily for 15 minutes while he filmed. “If the calf is not nervous, the mother tolerates you, and there are good vibes between you. The calf was sleeping, and would go up to breathe and then return every few minutes, swimming back underneath the mother. He even opened an eye, saw me, and closed his eye again.”

But the day he captured a humpback whale giving birth on camera three years ago in Polynesia counts as perhaps his most unforgettable moment in more than 50 years of diving.

“I’ve spent 66 weeks of my life filming humpbacks on 22 shoots so you could say I’ve got to know them. I was in the right place at the right time to see the little one coming out.”

However, with the mother surrounded by 10 aggressive males all vying to mate with her, Didier witnessed the heart-wrenching sight of one male trying to drown the new-born calf.

“The males were releasing a lot of bubbles – a sign of aggression – and this one was coming on top of the calf to try and kill it so he could mate with the mother. I watched the calf swimming super-fast to escape while the mum was trying to protect him and save his life. It’s nature, you are the witness and that’s it.

“The female returned four times to me. I was between the end of her pectoral fin and her eye. I didn’t know if she was asking me to watch her baby being born or protect her from the male - I’ll never know. The calf did not die. It was a very strong moment in my life.”

Didier’s goal now is to encourage mankind to re-establish a respectful relationship between humans and these majestic aquatic mammals.

“Over 30 years ago when I first started filming whales, it was difficult to approach them because what they remembered was being hunted by man,” he says. “But the babies know that man is not dangerous anymore. They enjoy coming to see you and play with you, they show curiosity.

“Scientists who say you should not approach or disturb whales are talking rubbish. People should swim and dive with whales if they are approached by them. We need to break this chapter of saying that it is a bad thing.

“I’m happy to be my age now and be able to have done things without needing permits and controls. I’ve had not just an amazing career but an amazing life.”

Read Next

Lindblad Legacy Anchored in Conservation

To the Ends of the Earth: The Extraordinary Adventures of Henry Cookson

Into the Blue: Exceptional Underwater Adventures with Rodolphe Holler