Copenhagen’s Alchemist Mixes Gastronomy with Social Impact

Alchemist features what the chef coins “holistic cuisine,” connecting culinary, visual and performing arts and design to science, technology and social impact for a “dramaturgically-driven sensory experience.”

Once upon a time, I fell down a “rabbit hole” in Copenhagen, Denmark into a multisensorial fantasy world of gastronomy, art, science, storytelling and social activism. The experience was in a former set warehouse of The Royal Danish Theatre on an old shipyard in the industrial neighbourhood Refshaleøen. Today the warehouse hosts one of the world's most exquisite and memorable restaurants, which serves a “50-impression” tasting menu in five acts like a fairytale.

Alchemist, the 2,200-square-metre brainchild of 33-year-old Danish chef and co-owner Rasmus Munk, is a darling in the culinary world with two Michelin stars and high rankings on all global lists. Munk himself was just named top chef in the world at the 2024 Best Chef Awards in Dubai, epitomizing the theme of “(R)EVOLUTION,” pushing the boundaries of what is possible in the kitchen and beyond.

Munk opened his first Alchemist restaurant in Copenhagen in 2015, which was a mere 100 square metres with 15 counter seats “like a sushi restaurant,” he says, serving 40+ thought-provoking dishes a night. With the help of billionaire financier Lars Seier Christensen, who invested nearly €11 million, Munk took Alchemist many levels up with staff, theatrics, research, innovation and 20 times the space. Seven months after Alchemist “2.0” opened in its current location in 2019, it received two Michelin stars. Two weeks later, the pandemic shut its doors for a while. When it reopened, there was a 10,000-person waiting list to get in. It’s been booked solid ever since, Munk says. And for good reason.

Image credits left to right: 1 Kim Holtermand; 2-4 Soren Gammelmark

Alchemist features what the chef coins “holistic cuisine,” connecting culinary, visual and performing arts and design to science, technology and social impact for a “dramaturgically-driven sensory experience.” He focuses on flavour, high-quality ingredients and skillful preparation, while pushing boundaries beyond the plate with dishes that give pleasure or “meaningful disgust” (think of an IV bag filled with a blood-coloured sauce that’s poured over a lamb heart). Munk aims “to start conversation through food and use that as a communication tool – a way to express beliefs, thoughts and statements – and [inspire] debates around the table.”

His holistic cuisine “stimulates and interacts with all five senses” as well as the intellect by challenging preconceptions of a meal, introducing international ingredients and food concepts, supporting biodiversity and sourcing sustainable supplies with a farm-to-table approach. Alchemist likens itself to Paulo Coelho's book “The Alchemist” because it is not until the protagonist sees the whole of all the elements that gold appears.

ACT I

Akin to “Alice in Wonderland,” my seven-hour Alchemist experience was like a fantasy. It began with two-ton, bronze, tree-like, self-opening doors beckoning me to enter. Still life (a torso sculpture) and real life (staff) ushered me behind a curtain into an artful, black and white “experience room” for Act I called “Perspectives.” A performance artist matching the room led me by the hand as a booming voice from above guided me through philosophical musings about identity. It was a cleansing of the mind to prepare me for a cleansing – rather sensory bombing – of the palate. The first tasting started with “Square One,” a crispy square of gelified apples, that metaphorically made me “consume” my self-image.

“Most chefs are thinking about flavours and ingredients and get inspired from that … like ‘This is what I want people to taste,’” Munk says. “For me it's more like, ‘What kind of story do you want to tell? Or what is the frame of this and how do we communicate through this?’ And then to make it taste good … with the best ingredients and whatever's in season.”

Image credits left to right: 1 Angela Dansby; 2-4 Soren Gammelmark

ACT II

Behind a door, I entered Act II in The Lounge, an elegant, low-lit room featuring a three-story wall of wine and white “wall of taste” with hundreds of jars of ingredients from around the world. The wall is a backdrop for chefs and food stylists, who artfully shape and assemble complex dishes using unconventional tools like tweezers and blow dryers. As I took in the visual feast, I was paired with a server who was only mine for the night, carefully chosen based on what the staff learned about me before arrival.

“Are you open-minded to everything?” politely asked Jogile Bulavaite, my tall, blonde, personable server and assistant general manager, who looked like my “bookend”. Being a hard-core foodie and already tipped off about unusual offerings from Munk, I gave a resounding “yes.” But even in the rabbit hole I did not expect to find such ingredients (spoiler alert) as a butterfly, pig and deer blood, lamb brain and ants. “Some things we take very much to the limit,” Munk notes. But it all must taste good, otherwise, Alchemist would have "a hard time selling new techniques, flavours and ingredients.”

Act II began with a drinkable “daisy,” Denmark’s national flower and the Danish queen’s nickname. It was made of foam flavored with mandarins, saffron and yuzu as well as frozen citrus pearls. The yellow “daisy eye” was served in a silver flower that Bulavaite put in a vase on my table after drinking. She then gave me the option of choosing from among 10,000 bottles of wine, including rare finds like Krug 160th edition Grande Cuvée Brut and 2012 Brunello di Montalcino, or a mix of alcoholic and non-alcoholic beverages paired with each dish. The latter was an easy and excellent decision, including the best of all beverage categories – from excellent wines to bottle-aged kombucha and Junmai sake.

Act II was a series of one-bite appetizers, starting with a deep-fried, hollow bread sphere filled with smoke and topped with langoustine tartare, almond cream and caviar. Next was a freeze-dried Small Tortoiseshell, Denmark’s national butterfly, served on a crispy “nettle leaf” made from juiced kale, parsley and spinach, artfully displayed on a silver twig. (Butterflies contain almost three times the protein of beef and chicken and could be a sustainable protein source, Munk reasons.) Then came a cotton candy dumpling filled with fermented fish gel wrapped in bok choy and aromatic herbs; “space bread” made of freeze-dried soy meringue topped with Royal Belgian Caviar; and “The Perfect Omelette,” egg-shaped and made with egg yolks but not resembling an omelette at all. Its shiny, speckled surface resulted from butter and black pepper applied with ultrasound.

Image credits left to right: 1-3 Angela Dansby; Soren Gammelmark

ACT III

Bulavaite led me upstairs past the wine wall into an airy room with an 18-metre-diameter planetarium upon which 360-degree, provocative videos “force fed” social impact while dining. Act III in The Dome was a series of small dishes and videos in four scenes – Under Water, Dramatics, Origins and Sweet Relief – that corresponded to ethical themes.

“From a very early age … if there was some unfair thing happening in the world, I wanted to change it and make it right,” says Munk, who is deeply committed to social causes and charity. Climate change, sustainability, biodiversity, food waste, hunger, social inequality and animal welfare are his hot-button topics.

The “Under Water” scene began with “Sunburnt Bikini,” a ham and cheese “bikini toast” made of cryo-fried mochi dough filled with cheese and ham. It was served on a clear glass dish filled with sand from Barcelona, where the dish concept originated. Next was “1984” based on the dystopian novel by George Orwell in which the population is watched by “Big Brother,” akin to mis/disinformation in social media today.

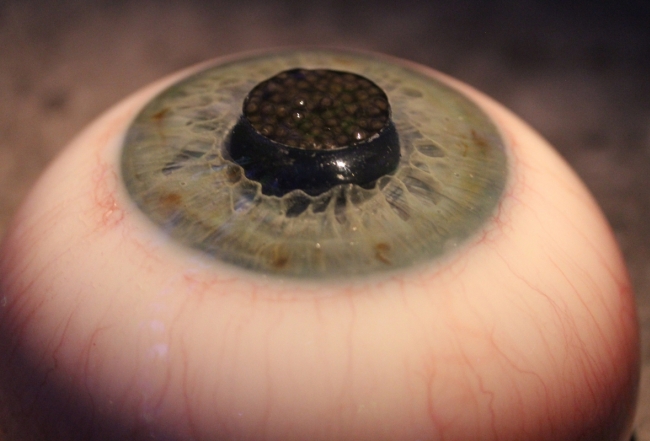

A large ceramic eye, modeled after Munk’s blue eye, featured an edible, giant pupil filled with black caviar, cream of corn, lobster tartare, pickled chanterelle mushrooms, lemon confit, olive oil and a sourdough bread crouton. I ate the “pupil” with a spoon made from cow horn of Jutland, the Danish region where Munk was born. Following was a reconstructed lobster claw made of frozen, butter-poached lobster claws and tails dipped in a vodka-corn starch mix and deep-fried until the coating became very aerated and crispy. It was dusted with fermented tomato and served with a horseradish-butter sauce.

As jellyfish, plastic bags and giant sea turtles with plastic rings around their necks floated in the overhead ocean, I ate what looked like a ball of plastic wrap. “Plastic Fantastic,” made from algae and fish skin collagen, hid tempura-battered white fish topped with tartar sauce. The subsequent king crab was also a departure from the norm without any crab legs. Instead it was made from Red King Crab tail and roe, parts normally discarded. The tail was stuffed with scallops as a metaphor for king crab predation on these shellfish plus lobster claws, shallots and citrus, then glazed with tomato and saffron. It rested on a thin bread crust brushed with shrimp paste, accompanied by a sauce made of dried seafood, cured ham and aerated tomato emulsion.

“The whole immersive dining experience [uses] knowledge and tools from other artistic fields and [mixes] it into culinary arts,” Munk says. “[It] creates a new experience because it is a melting pot of these different fields … I get a lot more inspiration from those fields than from other chefs.”

Scene 2, aptly called “Dramatics”, began with “Lithophane” derived from a 19th century etching technique. It featured a portrait in cream of Jerusalem artichoke on an underlit, glass plate to create a 3-D effect. “Tongue Kiss” required me to lick Spain-inspired sauces off a silicone tongue cast from a human. The sauces played upon each type of taste on the tongue, including garlic purée, fermented habanada peppers, roasted red peppers, sherry vinegar, anchovy, olive oil jam, lemon confit and fried breadcrumbs. “Food for Thought” was served in a sliced open, silicone human head/brain to showcase a bite of cherry meringue filled with lamb brain mousse and cherry gel, topped with a freeze-dried lamb brain crisp. A glowing, tropical cocktail with powder extracted from bioluminescent jellyfish helped me wash down the brainy concept.

Image credits left to right: 1-3 Angela Dansby; 4 Soren Gammelmark

“We've done lamb brain for many years now because it's an ingredient that you just discard normally,” Munk says. “[To] convince people to buy this element and request this part of the meal, we need to make it very delicious.”

“Origins” in Scene 3 challenged even more the way I look at food. It began with sheets of potato starch brushed with browned butter, roasted yeast and onion juice, baked in a vacuum for a puffy and crispy texture, and topped with a creamy, eggy foam and thin slices of Pata Negra ham shaped like a rose. “Hunger” featured two thin slices of rabbit carpaccio, edged with harissa sauce and dried flowers and draped over a silver ribcage the size of a rabbit but shape of a human. It was a powerful reminder of the prevalence of hunger and food distribution inequalities.

“Burnout Chicken” presented a chicken foot and leg in a cage about the same size as the space a chicken has in traditional commercial farming. To eat it, I had to “set the chicken free” by removing the leg from the cage and eating the top of it, which was made from a deboned chicken thigh stuffed with a soufflé of chicken, shrimp and green curry spices, glazed with tamarind paste and rolled in fried shrimps and puffed potato. The final “Footprint” was a cryo-fried, deboned chicken foot, pressure-cooked with spices and mushrooms, then coated with a sweet and sour sauce. The bones were used to make a broth to which a fermented shrimp-tamarind sauce was added. The flavourful broth was topped with jasmine oil.

“The fact that [people] here [spend] 5,000 DKK a meal and at the same time, there are 800 million people starving in the world ... it's relevant to put up some of these paradoxes,” Munk says. “It really provokes some of the established restaurant world.”

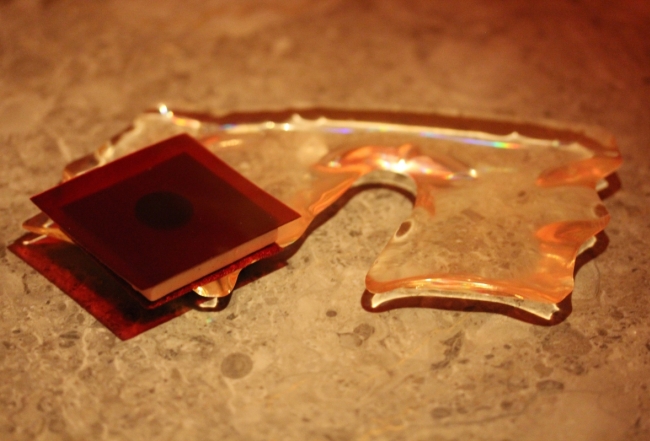

Scene 4 was “Sweet Relief”, starting with “Reflections”, a nod to identity with a “mirror prism” square made from layered blackcurrant gel that refracted a rainbow. The square was attached to an abstract glass plate with vanilla-olive oil ice cream and a chocolate crisp. “The Scream,” named after Norwegian Edvard Munch’s famous painting, was a mini, edible version of it, which became more acidic in taste from bottom to top. It was a gastronomic metaphor for the rising intensity of the painting with “canvas” flavours of saffron, Cointreau, liquorice and mandarin. While rushing blood cells and a beating heart displayed in the dome, “Lifeline” – a giant blood drop made of a pig blood ice cream shell filled with wild blueberry jam, pig and deer blood, and juniper oil – was served to raise awareness about the importance of blood donation (a QR code on my plate led to a blood donor page).

“I know that this [dish] would challenge most of our guests,” Munk admits. “The easiest thing would be to just put more berries and chocolate into it and then everybody would be very happy about it. But then it doesn't challenge you enough.”

Image credits: 1, 3, 4 Soren Gammelmark; 2 Angela Dansby

ACT IV

To cleanse the mind again before dessert, I entered another “experience room” filled with hundreds of clear, plastic balls that the performance artist and I threw into the air. Aptly called “Freedom” while playing George Michaels’ tune, Act IV caught me in the act of child-like behaviour, plunging into the balls, as reflected in mirrored walls. (The performance artist is among around 100 staff, including about 40 chefs, a gardener and ingredient curator, video maker, and music producer/composer.)

ACT V

Then I was led to Act V, “The Balcony,” in a cozy, top-floor lounge with a fireplace. It began with a rare Japanese tea and “Guilty Pleasure,” a 70 percent chocolate bar with a customized wrapper made of biodegradable plastic. The bar was filled with mango jam, roasted peanuts, milk chocolate, salted caramel and crispy cacao. Using chocolate sourced from a Congolese farm that guarantees ethical labour, it was a statement against child labour in cocoa-producing countries. “Amber” looked to be just that, complete with two dead wood ants trapped inside honey and ginger candy encased in beeswax and sugar. “Cubic Margarita” was a mini, solid version of the classic cocktail set with a red seaweed gelling agent, frozen to -35 °C and served on an icy, thermal plate. “In a Nutshell” looked like a striped, wooden flower with a crispy shell of caramelized milk and cacao filled with milk chocolate-hazelnut cream.

Last but not least, I was served an edible mustache based on a cake meaning “Grandfather's beard” in Danish. It was filled with blackberry marmalade and vanilla meringue and glazed with gold-flecked chocolate.

After these spectacular treats in Wonderland, I understood why Alchemist sells out every time it releases “tickets” and is worth its weight in gold (it starts at €660 per person for food only and €900 with the least expensive beverage pairings).

In keeping with the rabbit hole, my experience ended with a cocktail called “Hunt,” rabbit blood-coloured and made with vodka distilled with rabbit ears (Munk strives to use every bit of his ingredients). The mixologist brought the vodka bottle to my table to prove it. Was I dreaming?

My full stomach told me the glorious, long fairytale was real. I emerged from the “rabbit hole” after midnight giddy and mesmerized, wishing I could stay even longer. “Once upon a time” at Alchemist was in fact once upon a lifetime.*

* Note Alchemist regularly changes its experiences and dishes. The author dined there in March 2024 so readers who go there should be completely surprised.

Image credits: Angela Dansby

From Junk Food to Stratospheric Dining

During COVID-19, Rasmus Munk, chef and co-owner of Alchemist, founded Junk Food, a non-profit charity that provides meals to the homeless in Copenhagen. It used expiring ingredients that had no home with restaurant closings during the pandemic. Today, the privately funded Junk Food produces about 150,000 meals a year – with the goal of half a million – to alleviate hunger among Denmark’s homeless.

Alchemist also has several research collaborations with leading universities, such as the University of California at Berkeley, University of Copenhagen and Massachusetts Institute of Technology, as well as commercial partners. In 2023, Munk established Spora global research centre blocks away from Alchemist. This 1,000-square-metre facility has a research kitchen, microbiology labs, and 3D design and sound studio. It is currently focusing on upcycling waste products from the food industry and developing new protein sources like insects.

In Q1 2025, Munk will make history by orchestrating the world’s first immersive dining experience in space. In partnership with SpaceVIP, which offers luxury space travel experiences, he will serve dishes inspired by the impact of space exploration on humanity in the last 60 years. The six-hour journey will be on the world's first carbon-neutral spaceship, Neptune, where six explorers will enjoy a meal of a lifetime while watching the sun rise over the earth's curvature. No training or special gear will be required as Neptune is a pressurized capsule lifted gently by a SpaceBalloon™, not a rocket, to ascend from the Florida coast to 100,000 feet above sea level. At roughly €457,000 per ticket, all proceeds will go to the Space Prize Foundation, which promotes gender equity in science and technology.

Angela Dansby is a freelance lifestyle writer in Brussels, Belgium.

Image credits top of page: Portrait of Rasmus Munk by Kim Holtermand; Butterfly by Soren Gammelmark.

Read Next

How Chef Eric Ripert Makes Le Bernadin Top of La Liste

La Liste: The First Global Restaurant and Hotel Guide

Just Desserts: Sweet Talk with Michelin Star Pastry Chef René Frank